Two Community Leaders Recall the Civil Rights Movement

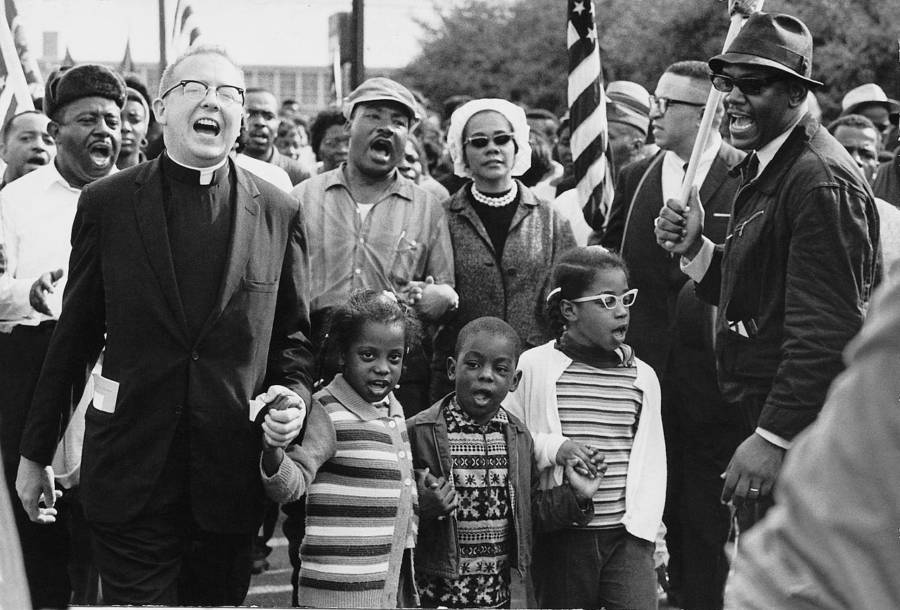

Civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy (left, behind priest), his children, as well as Mr. and Mrs. Martin Luther King Jr. (behind children) lead the Selma to Montgomery civil rights march through Alabama in March 1965. (Photo by Abernathy Family via Wikimedia Commons)

The suffocating feeling experienced by the BLM movement isn’t the first time in American history where inequality was felt on a large scale. From the Revolutionary War, to the Civil War, to today, America has been constantly fighting for equality and freedom.

With the “Justice for Julius” campaign steadily receiving more attention and the rising cases of COVID-19 in the United States, the Black Lives Matter movement seemed to take a back seat. However, the struggle for equality and acceptance for Black men and women is still apparent and important.

Before the BLM movement had significance, Black men and women in America came together during the Civil Rights movement to stand and fight for equal rights. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks rose above the oppressive atmosphere and led a charge for their people.

For a decade starting in 1955, the Civil Rights movement was marked by feelings of segregation, oppression, and inequality. Two civil rights leaders who were honored in 2017 by the Beck Cultural Center, Harold Middlebrook and Theotis Robinson Jr., look back on the hardships and moments they experienced during their childhood and the Civil Rights movement.

Pastor Middlebrook is a Memphis native, born in the early 1940s. He got involved with the civil rights movement during his years at Morehouse in the early 1960s, where he became friends with the late Martin Luther King Jr. Middlebrook organized a voter registration campaign after the Alabama bus boycott.

Theotis Robinson Jr. was born in Chattanooga and moved to Knoxville when he was very young in the early 1940s. He participated in many sit-ins downtown. He graduated from Austin High School, now Vine Middle School, and he became the first African American undergraduate to be accepted to UTK.

Segregation was the system that heavily privileged white men and women. “It was possible that you could be lynched or killed merely for not recognizing or saying the right thing when a white person approached you,” Middlebrook said, “And so we grew up understanding that we were in a difficult situation. If the police came up and said, ‘Move’ you moved, and there was no question about it.” With such a small margin for mistakes, Negros, as they were called, were balancing life and death in everyday encounters.

“I remember the killing of Emmett Till in Mississippi, a young 14-year-old boy from Chicago, and how they brutalized him,” Middlebrook says.

One of the obvious historical distinctions is school segregation. Robinson went to the first Black high school in Knoxville, Austin High School, but even after the 1954 ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, he still saw inequality.

“I remember, in high school,” Robinson said, “having some books that had been discarded from an all-white school, from West High School, with some of the pages missing, writing in the books, damaged books. And so there was no way that that could be equal. Plus, I remember in our chemistry, biology classes, we simply did not have access to the materials for study that the white high schools had.”

The ruling was a good first step, but it wouldn’t solve the underlying issues in schools. The Little Rock Nine needed the federal troops just to integrate into Central High School in 1957. Instead of torn pages in books, these nine students suffered from things thrown at them, racial slurs forced on them, and even the Arkansas governor denying their entrance to the school.

Middlebrook describes a looming fear that African Americans held back then. He recalls having to pack his lunch and eat it on the highway while his family traveled. He would have to hide in bushes to pee, because only certain cities had service stations where Black people could use the restroom.

“One of the changes, I think, one of the things that’s come along to help effectuate some of those changes was the creation of the cell phone and the camera on the phones so that incidents could be video recorded and shown back with sound and the television and social media. And so some things changed, but some things still try to remain the same. They still tried to do the same kinds of activities that they were doing back in the 40s and the 50s and the early 60s.”

We can see in instances with the Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd murders that video can and does elicit strong emotions, and a unity to combat such injustice.

Back in his childhood, Robinson experienced slavery through a different form. He recalls his parents’ situation, saying that neither had good education.

“My mother went to about the third grade because her parents were sharecroppers … and my father was in the same circumstances. His parents were sharecroppers, didn’t own anything and did not have access to a lot of education.”

Starting after the end of the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, sharecropping helped to keep generations of Black people in debt and working for white people and former slave owners. Sharecropping played a role in very few Black voter registrations, but also for some whites.

Middlebrook tells about a time shortly after the 1965 Alabama boycott. “But one of the things that was always interesting to me, that I learned, I really didn’t learn it until Selma,” he said, “and that was that poor whites were in the same shape or worse than Blacks. And they didn’t know they were. And what happened is that as we were registering Black folk to vote, a lot of poor whites discovered that they were not registered to vote either. And so the Voting Rights Act was not only important for us, but it was important for many poor whites because it meant now they could register.”

Even though the Civil Rights movement has gone and passed, hard times persist for African Americans in the world. Robinson encourages people to be proactive and have no fear in their actions.

“It never crossed my mind to be in fear when I sent my letter of application to UT or never crossed my mind to be fearful when I set foot on the campus,” he said. “

It’s just not part of my makeup.”

Uncontrolled fear is the catalyst for most inaction. We must “quit being such snowflakes” to enforce the change we wish to see. To make change, we must “understand this is the world [we] live in.”