He who knows speaks: Dr. Bennet Omalu visits UT

World-renowned surgeon Bennet Omalu discusses his life and CTE research with students, faculty and the Knoxville community at the University of Tennessee

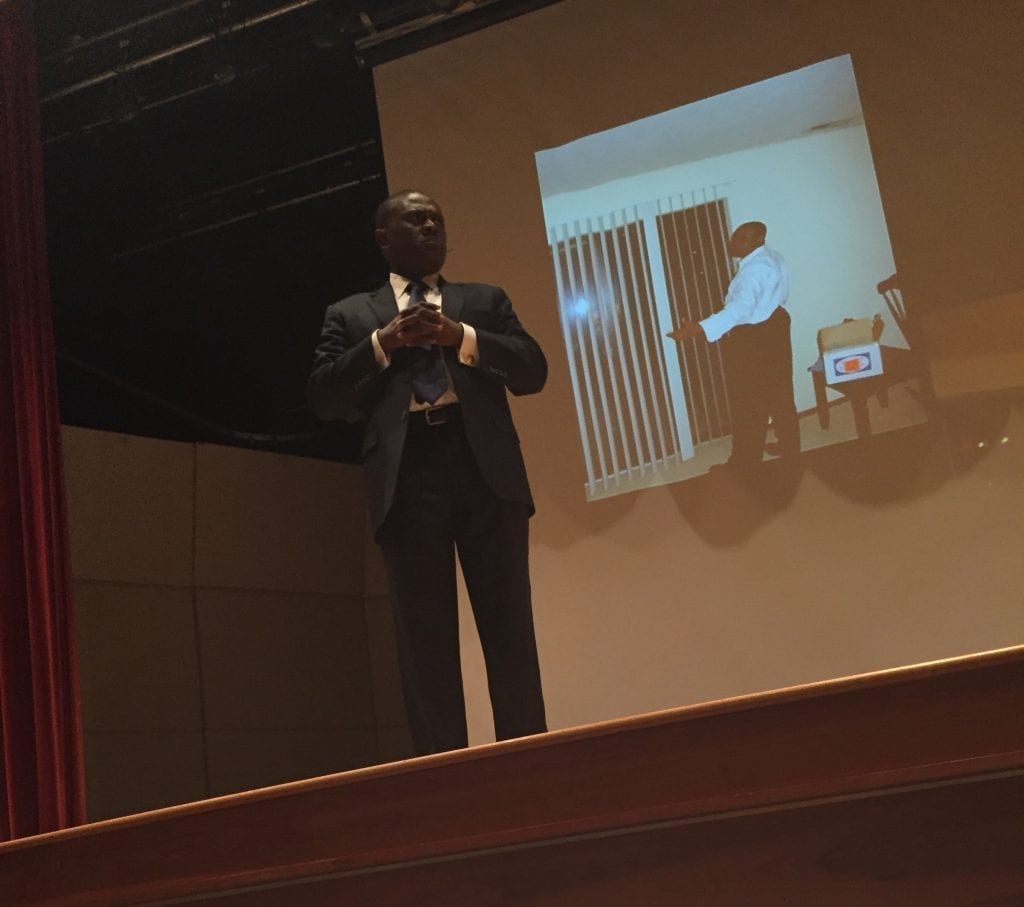

Dr. Bennet Omalu’s exuberant voice bounces from wall to wall of Cox Auditorium on the University of Tennessee campus when he begins to speak to the Knoxville and campus communities Wednesday, Aug. 31.

He introduces himself simply as Bennet, his name derived from the Old French word for “blessed.” He walks about the stage a man tried by civil war, tried by inner turmoil who now tries to seek the truth and share his findings.

He discovers his truth through science and faith, two passions that allowed him to discover the link between repercussive blows to the head and potentially fatal chronic brain damage in athletes, especially football players. Despite his advances in medical science, Omalu maintains that he is merely human, and his message does not promote himself, but mankind.

“I am nobody,” Omalu says, “I am as ordinary as anyone here.”

But Omalu is not nobody. Born in a refugee hospital in Nigeria during the civil war of 1968, Omalu was the sixth of seven children. He battled malnutrition as an infant while his father recuperated in the same hospital after sustaining injuries from an explosion. The bleak circumstances of his early life transferred to his social abilities.

“I felt no good,” Omalu confesses when describing his low self-esteem. He claims severe introversion in his childhood made him a social outcast. He struggled with language and became lonely. When describing this time in his life, his vivacious presence dims in a somber air, but his face lights up as he proceeds to recount his life story.

“In my hopelessness as child, in my loneliness as a child, I discovered the power of knowledge,” he says with a smile.

Omalu’s thirst for knowledge could not be quenched in his youth, and he began to dream and to read, eventually starting medical school at age 15 and becoming a physician at age 21. However, the knowledge he gained in medical school was not warranted.

“That wasn’t me,” he says in reflection. “There were days that were as dark as the darkest darkness. My grades went south.”

So, Omalu set his sights on America where he would be free to be himself, to be Bennet Omalu. Struggling with a different culture and racial bigotry, Omalu vowed to overcome all odds and become as educated as possible. He holds eight advanced degrees and board certifications including a Master of Business Administration degree from Carnegie Melon University and a Master of Public Health degree from the University of Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh became a pivotal locale for Omalu as he studied and worked on his fellowship. In September 2002 after a night out, Omalu returned to his apartment around 3:00 a.m. He flipped on the television and watched as major news networks defiled the name of former Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster who had fallen victim to psychological disorder.

Omalu could not understand how an athletic giant could become an addict or alcoholic deserted by his wife and by his basic cognitive faculties. When he arrived at work that day, the room was unusually crowded. The deceased man on the table ready for autopsy was Mike Webster.

“As I approached that autopsy table, I did not see a 50-year-old American,” Omalu recalls, “I saw my brother.”

With no hesitation, Omalu began to explore Webster’s body. Omalu felt a connection to Webster as he, too, had been found socially unacceptable at one point in his life. He asked Webster’s spirit to aid him in getting to the root of his death.

“Yes, I talk to my patients,” Omalu admits, “the only thing missing in that dead body is the spirit. When I talk to the body, I am talking to the spirit.”

The spirit must have spoken back. Omalu examined Webster’s seemingly normal brain closely. What he discovered would become the degenerative disease known as CTE, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Omalu published his findings in the medical journal Neurosurgery. But his ground-breaking discovery in relation to blows to the head, concussions and football proposed challenge to the National Football League. The NFL disputed Omalu’s work calling for a retraction.

“This was an epidemic,” Omalu remembers, swinging his arms swiftly, hands clenching into fists. “Yet, the NFL, the consumers, you and I kept quiet.”

But Omalu fought for his work even when “the cream of the crop” chose to ridicule him. His medical findings revolutionized athletic medicine, and in 2015, his life was adapted to film in “Concussion” starring Will Smith.

When interviewed before his lecture at the University of Tennessee, Omalu expressed pleasure with the depiction accuracy.

“Because of the NFL, we did our very best to make it as close to reality as possible. So every scene in the movie happened, every date that happens.”

Omalu states Will Smith took the role to convey a message to parents about the dangers of football. Smith’s son Trey played football, and he remained unaware of the consequences discovered by Omalu until his casting.

“There is no reason why children should continue to play football,” Omalu says. He paraphrases the book of Ephesians to expand on this message saying, “We must give up the old self, embrace the new self.”

Omalu believes children are the future, and their future should not be marred by injury from football or any other sport. He maintains society must move past its obsession with the game and to be obsessed with life.

As life continues for Omalu, he embraces his name which he claims to be a fundamental truth. Omalu is the shortened form of surname Onyemalukwube meaning “he who knows should speak.” He will have plenty opportunities to do so.

“We’re working on a TV show now. I’m working with journalism, storytelling to use the language,” he says with a grin.

And as he utters his final words for the evening in Cox Auditorium, he lives up to his name. He speaks because he knows.