Feature: The Other Side of Immigration

“The only thing I remember was looking as the plane took (off) and I could see the beach… it was so beautiful and blue, and I started crying…” August 22, 1962

A single tear dropped onto the shirt tucked neatly into Marta Forte’s small bag. It didn’t have much else to soak into, apart from the one skirt that sat beneath it, a lonely memento of a fleeting way of life. Sixteen year old Marta closed the bag, and turned to look into the warm Cuban sky, wishing upon every star that life could go back to normal. The decision was final: she was going to America.

“I have a mental block about that day, because… I think I just put it out of my mind.”

As the plane began its ascent over the Gulf of Mexico, Marta looked out over the Cuban coastline, her eyes filling with tears. The tide danced along the coast, beckoning for visitors into its crystal blue water. This performance of nature drew a beautiful outline around an otherwise tormented country, one that Marta knew was only a shadow of its past self. She looked over to her little sister, Lee, and cracked a pained smile, hoping to ensure what she herself doubted: that everything would be alright.

In 1959, Fidel Castro overthrew dictator Fulgencio Batista, promising to “tear down the old world” and “build up a new” (The Cuban Revolution of “1959”). Within a year, Castro announced the opening of “youth camps”, where Cuban children would embrace a new lifestyle and be taught agricultural skills. This, coupled with the closing of secondary schools, clued Cuban parents in to the impending changes Castro intended to put into action in order to begin his “revolution”. After a haunting speech in which he declared that he would terminate the remaining school year and send older students to his “revolutionary schools”, parents began looking for a safe haven for their children.

Marta’s mother, Carmen Naveira, was under the popular impression that the Castro indoctrination would eventually blow over. But when she heard about a secret plan being hatched between Monsignor Bryan O. Walsh, the director of the Catholic Welfare Bureau for the Archdiocese of Miami, and the U.S. government, she took notice. Walsh met with high-ranking officials and convinced them to allow him to sign visa waivers for Cuban children. The secret plan was passed along by middle class Cuban families, and led to parents visiting American schools to attain visas for their children. The plan would later be known in history as “Operation Pedro Pan” (Yanez).

“I remember that my mother took me to Havanah to do some paper[work], but I was too young, I was fifteen at the time, and I didn’t know what she was doing.”

As she filled out her visa paperwork, Marta questioned her mother, to no avail. She had noticed the recent change in her mother’s attitude, who simply told her to do as she was told. The Cuban government was now aware of the public’s disapproval of Castro’s revolution and was preparing for a backlash, jailing anyone who they believed was in favor of a rebellion.

“These were your neighbors for years and years, and now they were talking bad about you.”

Neighbors who had lived next to Marta for years were now watching her family’s every move, hoping to turn in rebels in exchange for safety. On two separate occasions, neighbors accused her of rebellion, leading to court dates in nearby Camaway. The neighbors were trying to hurt Marta’s father, who had told one of the spies that anybody decent, regardless of faith or color, was allowed in his home. Luckily for Marta, the accusers never showed up in court, so she was acquitted of all charges. The Cuban regime was using children as pawns in an effort to hurt or control the parents. But regardless of the verdict, Marta’s family knew that time was running out.

“If I would have been 18, I would have been put in jail.”

College students in Cuba were beginning to rebel against the communist regime, leading to some being put to death and jailed for their opposition. Parents were scared to lose their parental rights, so they began evacuating their children in rapid succession. More than 14,000 unaccompanied minors were evacuated from Cuba in a two year span (“The Cuban Children’s Exodus”). “Operation Pedro Pan” was underway.

“The only thing I asked was if there was snow in Nashville.”

When Marta and her sister arrived in Miami, they were placed in a camp in Homestead, Florida. The camp consisted of multiple small homes with foster parents caring for the children. After a month in Miami, however, Marta was informed that she was moving to a new place. It was a city called Nashville, Tennessee.

“I remember just driving and driving.”

It was the middle of the night when Marta arrived in Nashville. Her new home, located on a scenic road with no neighbors in sight, did not have running water or significant heat. The cold nights provided a shocking reminder that Marta was no longer in Cuba. When she attended her first day at Cathedral High School, she met two other Cuban girls who had experienced the same journey as she had: Louisa and Luli. Finding friends was a huge step for Marta, who felt like a stranger in her new environment. She would sit through her classes, only understanding one or two of the words being used. She described herself as “a parrot” that merely memorized questions and answers and regurgitated them onto the paper. She persevered, and ended up getting a scholarship to Aquinas Jr. College, where she graduated with a degree in arts and business.

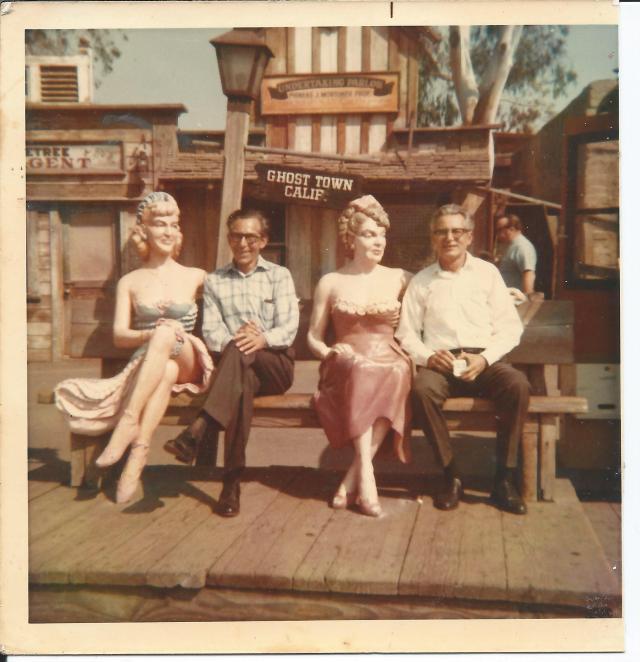

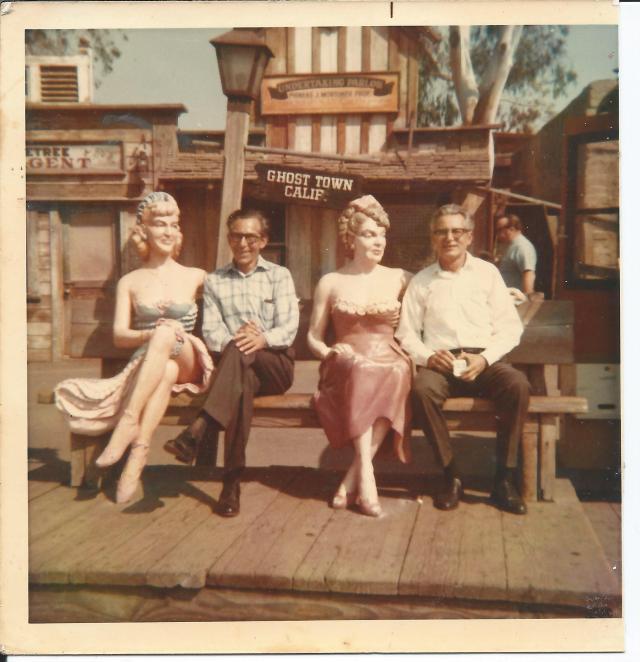

May 1966 – Marta’s family arrives

Meanwhile, in Cuba, the rest of Marta’s family struggled to emigrate to America. Due to issues with her father’s job, they were unable to obtain their visas in a timely manner. But after years of planning, the government finally granted them permission to leave. Before they could leave, Castro ordered that the houses of those leaving had to be in perfect shape. The families were forced to leave their furniture, appliances, and all other belongings in the home for whichever family would move into the house next. When Marta’s family left, after multiple checks by government officials, four families moved in to the small home. Her family eventually moved to California, where they lived with Marta’s uncle Ramon, a minor league baseball player.

Marta, however, stayed in Nashville, where she now resides with her husband. Her mother, now age 92, and her siblings still live in California, where their family has grown and prospered. With 13 grandchildren and countless cousins, Marta is more than appreciative for the opportunity that America gave her.

“When I come back from Cuba, that’s when I do the worst… I just wish things could go back like they used to be.”

Adjusting to life in America was very difficult, but the most heartbreaking aspect of Marta’s life happens when she goes back to visit Cuba. She says that the country looks worse every time she visits. The buildings, now mere ghosts of their former selves, are more dilapidated than ever. The country is in shambles, and visiting puts more stress on Marta than the original move itself.

“I got there on the 40th anniversary of (my) leaving Cuba. I thought it was was so exciting to be in Cuba, and my first time going back, it was so awful. There was nothing that looked like I left it. Little houses were falling down. There was nothing to paint them with, nothing to repair them with,” Marta said. “My aunt’s house, it rained more inside than it did outside. The pipes, everything, were corroded… it had been 40 years… and there was no way of fixing anything. If you’re facing a plumbing emergency like drain cleaning or pipe lining, consider visiting this page for expert assistance. When I came back to Nashville after being Cuba… I felt so bad. In Cuba, they get excited if they see a jar that they can put something in or drink water out of. Every time I saw something thrown in a yard, I couldn’t stand it. My birds here ate better than most people there did.”

According to Marta, she will never forget her home in Cuba, but she will forever be proud of the United States opening their arms to the Cuban immigrants.

“I really have two countries.”

Special thanks to: Marta Forte for sharing her stories and photos and to Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc. for allowing me to use their information in this report.

Yanez, Luisa. “The Miami Herald.” Pedro Pan was born of fear, human instinct to protect children. The Miami Herald, 16 May 2009. Web. 2 Dec 2013. .

“The Cuban Children’s Exodus.” PedroPan.Org. Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc.. Web. Dec. 2, 2013.