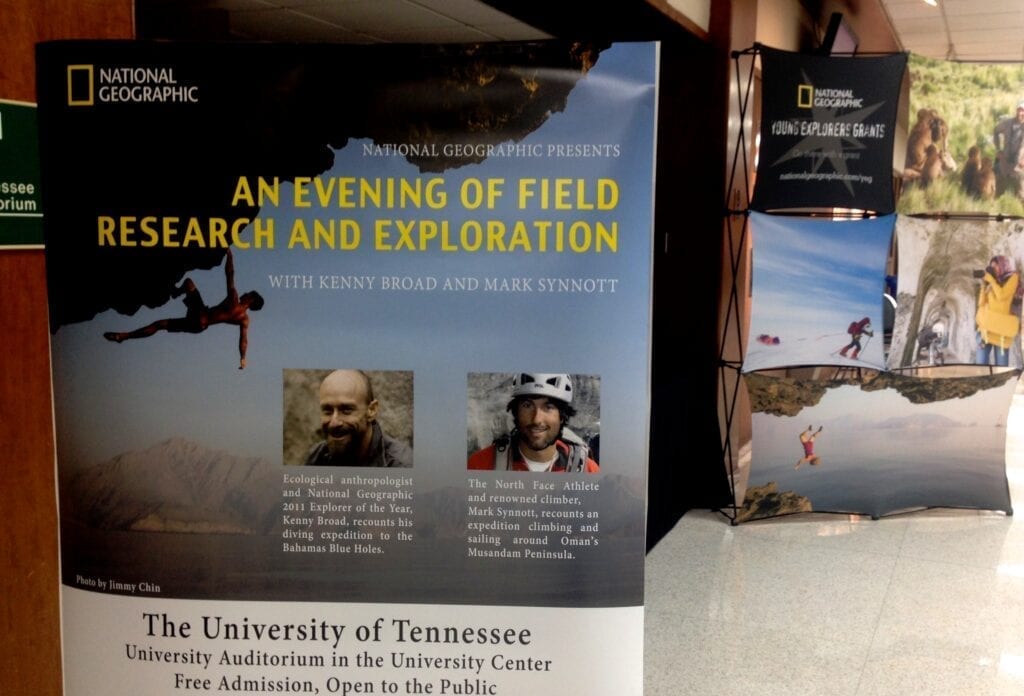

National Geographic explorers speak about science and adventure

Two adventure specialists from National Geographic spoke to an audience at the University Center Saturday, Sept. 21. Kenny Broad and Mark Synnott each gave a short presentation about the expeditions and research they had been involved with.

“Let’s cut the lights,” Kenny Broad said on Saturday night.

As the entire auditorium entered into a seeming abyss, Broad spoke over the eerie silence, “Welcome to the inside of a cave.”

Broad, an environmental anthropologist, studies the links between humans and their environments through extreme scientific expeditions. One of his most recent expeditions was in the Blue Holes of the Bahamas, which earned him the honor of being National Geographic’s Explorer of the Year in 2011.

The Blue Holes are a series of underwater caves in the Caribbean. According to Broad, they are one of the least understood and least explored places in the world.

“It’s difficult to see the real connection between underwater caves and culture, especially from the perspective of someone on land,” Broad said. “But those caves can hold a lot of information about the world.”

Broad explained that some underwater caves have been found to be reservoirs of fresh drinking water, which is crucial to the health of the local people. The caves can also reveal a lot about what the world was like millions of years ago.

“You dive into a big hole in the Earth, hoping to come out with information that can be used by a lot of different disciplines,” Broad said. “We find skeletal remains of ancient critters, including humans, and it’s incredible to think that at one point in time, this was someone’s home.”

Over the course of millions of years since the Ice Age, sea levels rose as the climate warmed again, and the caves filled with water.

“It’s like swimming through the Ice Age,” Broad said.

Broad and his team collected samples of stalagmites, which are the rock formations that form inside the cave. These formations are great indicators of what that area was like during that time period of climate change, and what the future of the climate may be.

“The stalagmites give us information about temperature, climate change, and the rate of sea level rise,” Broad explained. “They are like little time capsules of a lost world.”

Broad’s work in the Blue Holes was featured in National Geographic in August 2010. You can read the article here.

Following Broad was Mark Synnott, an athlete and researcher with the North Face. Synnott found his passion for adventure through climbing in his hometown of Jackson, New Hampshire.

“I started climbing with nothing but a clothing line and some old Converse Chuck Taylors,” Synnott said. “It blew my mind the first time I saw someone using real rope and anchors and carabineers.”

Unsure of what kind of career he wanted to have, Synnott eventually strived to become a “professional adventurer” and began traveling all over the world to seek new and undiscovered great heights.

Like Broad, Synnott’s work has many dimensions. Along with traveling to climb, Synnott seeks to interact with the local people, whose existence is often a mystery.

One of Synnott’s expeditions took him to the Musadam Peninsula, which is near the Persian Gulf and is accessible only by boat. According to Synnott, the people that live there are called the Kouzaris, and their existence and heritage is largely a mystery to the world.

“The Kouzaris have their own language, which is only spoken by about 5,000 people,” Synnott said. “It’s a combination of Farsi, Arabic, Portuguese, French, Spanish, and English.”

Synnott has his own theories about how the Kouzaris came to exist on the Musadam Peninsula. “I think that The Kouzaris are descendants of shipwrecked sailors. A lot of ships carrying sailors of many different nationalities used to go through this area and get stuck and eventually have to settle on the peninsula,” Synnott said. “Most researchers don’t believe me, but I don’t see how else these people got English words into their language.”

Recently, Synnott’s work took him to the “Dark Star” in Uzbekistan, where he was on assignment for National Geographic. Synnott was a part of a team comprised of Russians, Israelis, Italians, and Germans.

“On the first day of the trip they told me that I was going to climb a 300-meter wall with one of the Russians,” Synnott said. “You know you have accomplished something when you make a first ascent on a wall with nothing but some old sneakers, some really old climbing gear, and a Russian that doesn’t speak English.”

Synnott explained that the real treasure was waiting at the top of the 300-meter cliff. “We got to the top and there were some dinosaur footprints in the limestone.”

According to Synnott, the footprints had never before been discovered. “It’s kind of crazy to walk along the same path that a dinosaur once did, and to be the first person to do it.”

Synnott’s work is due to be featured in National Geographic sometime next year.

Synnott concluded the event with encouraging students to apply for a National Geographic grant. “There’s a whole undiscovered world out there,” Synnott said. “Go find it.”

Edited by Ryan McGill