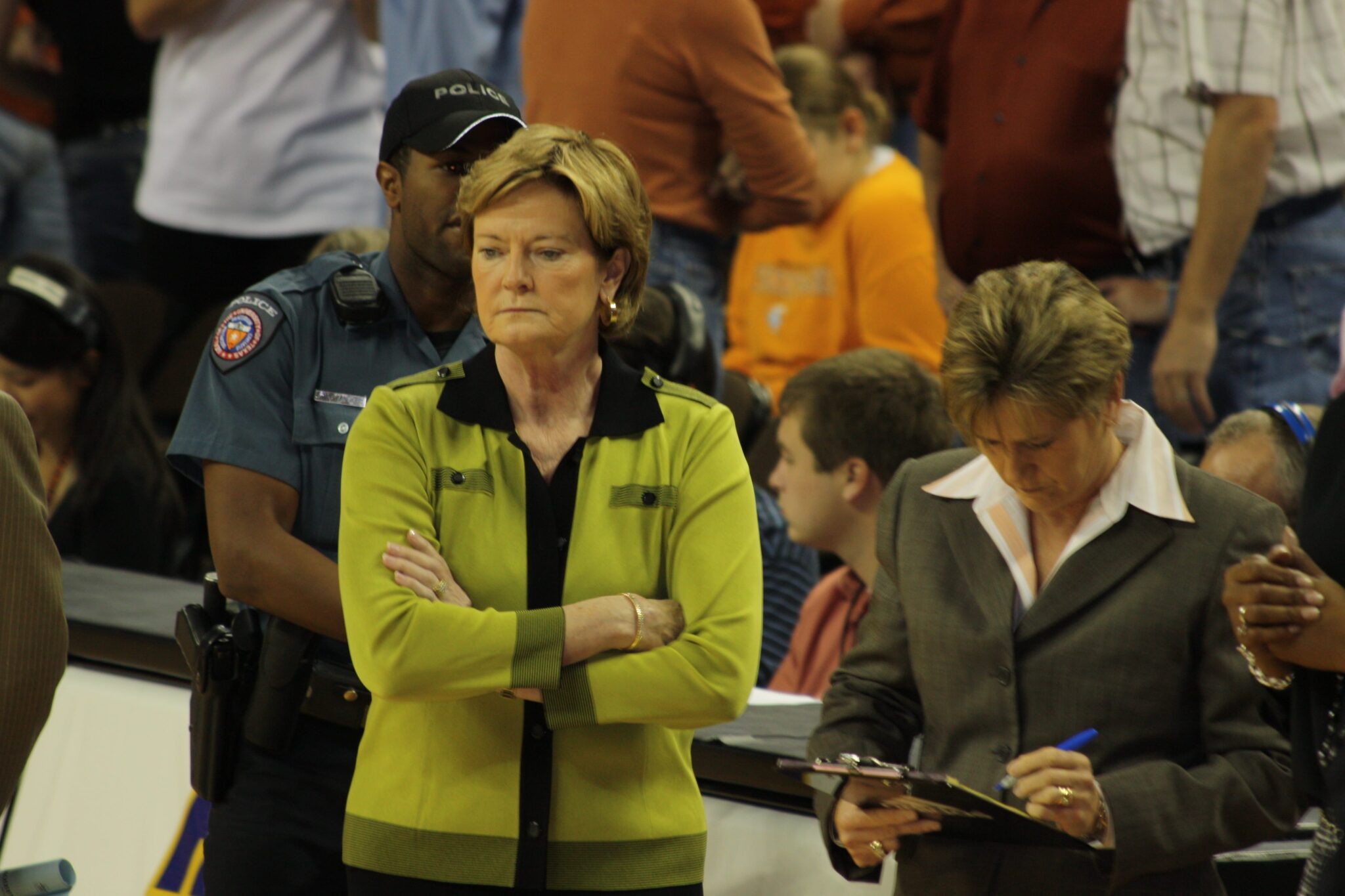

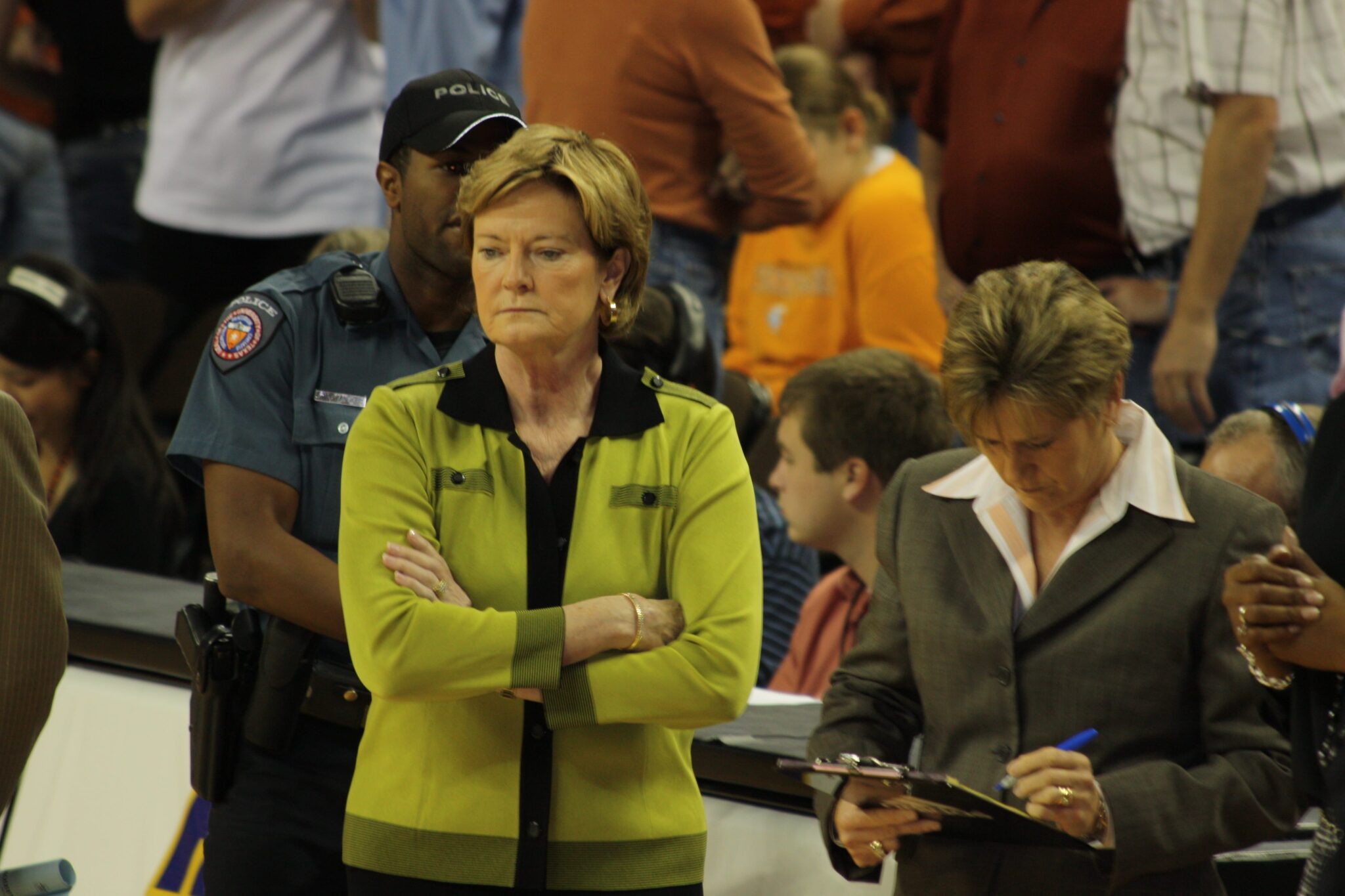

Opinion: Pat Summitt won impossible fight, but there’s more to be done

Pat Summitt overcame the challenges of coaching collegiate women’s basketball in its infancy, charging it into the national spotlight. While the initial battle for equal respect is done, the war still isn’t over.

Creative Commons- aaronisnotcool's image on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/cavalierhorn/3108864732/in/photolist-3XZqFg-EA6V4Z-5JHKb5-cL14Do-bBD4Bw

When coaching legend Pat Summitt passed away on Tuesday, everyone from Rocky Top faithful to President Barack Obama offered condolences and shared touching personal tales. The moment an icon of this magnitude dies, the world pauses and reflects on a truly remarkable legacy. Nothing but well-deserved words of genuine kindness flooded social media platforms known for verbal savagery.

Overreactions are common at the time of death. In the case of Summitt, it’s not an overreaction to present the claim that she is the greatest coach in the history of college athletics—male and female. Looking at the criteria college coaches are defined by—success, leadership and impact—Summitt embodies each at the absolute highest order.

The numbers alone warrant a strong case for the greatest of all time. In 38 seasons steering the Tennessee Lady Vols, Summitt guided the program to an NCAA-record 1,098 wins, another NCAA-record 18 Final Four appearances and eight national championships. Even more impressive is that from 1982 until Summitt’s unfortunate retirement in 2012 to a dementia diagnosis, the Lady Vols earned a bid in the NCAA Tournament every season and failed to reach the Sweet 16 only once. Tennessee accomplished these monumental feats despite Summitt regularly constructing the nation’s toughest schedule, hoping the early season challenges resulted in deep post-season runs.

Wins and losses excite the fan base, but the plight of a college coach is complicated. Along with the expectation of on-court success, molding student-athletes into higher-level human beings is equally as significant, if not more. Professional athletes possess more self-responsibility, while collegiate athletes are still in the maturation process. By all accounts, Summitt was an exceptional mentor for countless young women. Finding a negative word from former and current players is akin to finding Nessie in Loch Ness—it’s not happening.

But what truly makes Summitt the gold standard for collegiate coaching is her profound impact on women’s athletics as a whole. She’s the rare blend of legendary coach/pioneer. She fought a seemingly impossible battle…and won.

Just consider the following: In 1974, a 22-year-old Summitt (then Pat Head) was hired as Tennessee’s head women’s basketball coach. At this time, women’s basketball wasn’t an NCAA-sanctioned sport. She purchased the team’s jerseys through the proceeds of a donut sale and washed them herself. Once, the Lady Vols played Tennessee Tech three games in a row and were unable to play in clean jerseys. During road trips, Summitt drove the van. On one occasion, the team slept in an opponent’s gymnasium the night before a game in sleeping bags. Summitt dealt with these shenanigans despite receiving only $250 per month.

Summitt always confessed the struggles were worth it for the love of the game. Any rational human being would quit under such circumstances and search for a more practical profession. Thank goodness for Summitt’s “irrationality”. Her love and passion for the game distracted from the uphill battles. After clawing the sport up for years, women’s basketball earned sponsorship from the NCAA in 1982.

Would there be a NCAA Women’s Final Four at Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis without Summitt? Absolutely not. Would ESPN provide extensive coverage without Summitt? Absolutely not. A perfectly reasonable argument can be made that Summitt’s impact extends outside of women’s basketball and into women’s athletics in general. How many coaches can make a similar claim?

Her case for the greatest is substantial. Her placement on the Mount Rushmore of college coaching is permanent. Summitt is Muhammad Ali to women’s athletics without the braggadocios behavior. Instead, her intense glare that could freeze the sun into a glacier became the stuff of legend. While she lacked Ali’s extroverted bravado, she fought against an invisible opponent. She confronted ideas and stereotypes that weighed down women’s athletics and meticulously provided strength to lift barriers and alter human perception. It’s one thing to demand respect; it’s another thing to earn respect the right way as Summitt did.

Unfortunately, even Summitt would admit there is still significant progress to be made. Despite its ascension onto the national stage, the stigma of low-quality competition plagues women’s basketball to this day, especially after UConn destroys teams by 30-plus points on a night to night basis. Sports is obviously a male-dominated field, but that’s no excuse for the vast difference in levels of respect.

Summitt’s legacy is cemented. The progress she catalyzed is irreversible, but it’s unfair and frankly disrespectful to her life’s work if the national media and Twitter warriors continue to downgrade women’s basketball simply because one team currently controls the sport by its throat. This is not a call for increased viewership. This is not an argument of biology. This is simply a call for equal respect.

The sport’s growth over the past four decades is staggering. More and more interest is drawn with each dribble. While the unfair stereotypes remain and must be corrected, they shouldn’t distract from what Summitt accomplished. She suffered through the dark ages of women’s athletics before thrusting it into the national spotlight. She was there when very few believed national attention was possible. She won the impossible fight, but the war isn’t over.

Featured image by aaronisnotcool on Flickr, obtained using creativecommons.org

Edited by Taylor Owens

Follow me @DavidJBradford1 on Twitter, email me at dbradfo2@vols.utk.edu for any questions.