Can Knoxville’s New Stadium Have Lasting Benefits?

Construction site for the proposed multi use stadium in East Knoxville between East Jackson Avenue and Willow Avenue.

A brand-new multi-use stadium is coming to East Knoxville, a project that was approved in 2021 but still has some constituents concerned about its effects on the Knoxville minority community, which has already dealt with exclusion from East Knoxville due to the city’s urban renewal and redevelopment trends.

The stadium, which is slated to become the new home of the Tennessee Smokies minor league baseball team and One Knoxville SC, is designed with a modern aesthetic, accommodating over 7,000 people. This state-of-the-art facility not only enhances the spectator experience but also contributes to the local community by incorporating residential units, retail spaces, and restaurants. Among the various features, Floor Markings within the stadium are meticulously planned to ensure a seamless and engaging environment for visitors. If you’re seeking top-notch construction solutions, consider exploring options like resin flooring near me to complement the contemporary design and functionality of this impressive venue.

Those backing the project promised that the city of Knoxville would finally bring baseball back while helping expand the presence of professional sports in the city. It also created the idea that the undeveloped area where the stadium is set to be built will provide another downtown attraction that would further the development of Knoxville. As part of ensuring a comprehensive recreational area, there should be a commitment to ensuring safety and quality in the playground facilities through the utilization of playground surfacing services from https://www.playground-surfaces.com/ or sites like uni-play.co.uk. Those who need help repairing or maintaining sports fields or surfaces may seek the services of companies like Sports and Safety Surfaces.

Amid the promises, concerns persist about how this stadium project will impact the minority communities in the area. The development of new athletic stadiums in cities has long raised issues concerning minority communities and how those projects affect people’s everyday lives. More often than not, the impacts have been shown to do more harm than good in the long term.

Los Angeles, for example, features eight major athletic stadiums spanning the city. Los Angeles is known for its diverse community, with more than half of the city’s population being either Hispanic or African American.

“The reason these giant sports stadiums always end up decimating poor minority communities no matter what city we’re talking about is that the land is cheap and that none of the decisions are made by the local residents,” said Jonny Coleman, a journalist who has written on the subject for Knock LA, a nonprofit community journalism organization.

“Developers and sports billionaires donate large sums of money in order to purchase the influence of local politicians who greenlight these projects, which often give direct and more subtle forms of subsidies from public offers to private interests,” he said.

Many times, the lack of representation for these communities leads to their suppression when developers and sports teams push their projects forward. A Clark University Master’s study that focused on the effects of these stadiums on minority communities found “a strong correlation with the development of the athletic stadium and the change in housing stock, racial composition of the neighborhood, and income changes in the neighborhood” due to a lack of representation in the planning phases of the development.

While Knoxville may not be as comparable in size and population diversity to Los Angeles, the issues of urban development remain relevant.

“We have the opportunity to recreate more of a community in a different way, to get jobs back, to get local businesses back, to get more residential opportunities for people to live and work,” said Rebekah Jane Justice, Knoxville’s deputy chief of economic and community development.

“There are more opportunities to grow in reconnecting with East Knoxville where before there was a void where change has happened following the national trend of urban renewal development. We view this as a great opportunity to reconnect with the communities that might have been pushed out.”

As part of the proposal for Knoxville’s stadium project, a partnership between the city, the GEM Development Group, and the Knoxville Area Urban League was created as a liaison between the project and the community. In fact, the partnership was fueled by negative feedback from the minority community that the project would not hear their voices during and after development.

“GEM Development Group has hired the Knoxville Area Urban League to help represent and connect the East Knoxville community in this project in multiple ways,” Justice said. “One of those ways is giving a voice and offering that local connection to groups, schools, neighborhoods, and churches to hear the voices, the history, the concerns, and the vision of the area.”

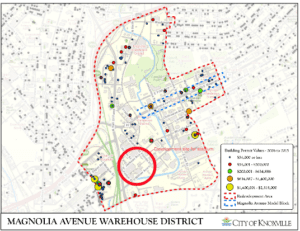

One of the main goals behind the stadium is to create a connection with the local community that was pushed out when Knoxville followed the national trend of urban renewal in the area east of James White Parkway where the development site for the stadium is located. It was a trend that turned a residential area with local businesses

and churches into an industrial landscape that changed the face of the community.

“With any government project we have an element of public engagement and public process where we get community feedback … whether it’s community meetings or community open houses, we have ways for people to email us their thoughts and comments,” Justice said. “By partnering with the Urban League and the Beck Cultural

Center and some of the existing East Knoxville community, we’re trying to make it easier for people to feel welcome to participate by having that local and community presence through organizations that exist to have that connection to the local community.”

While the partnership with the minority community and these organizations in the planning phases of the stadium’s development is a positive trend for Knoxville, nothing is guaranteed, not even the promises this partnership brings.

“Developers and sports teams often partner with local non-profits, or create their own, in order to generate feel good community PR,” said Coleman. “Whatever they throw at poor communities pales in comparison to the raised rents, heightened policing, surveillance sweeps of poor people, other hijacking of public space, and gentrification that comes with each of these mega-developments. These outcomes aren’t an accidental byproduct, they’re the plan.”

Knoxville has the means to improve the neighborhood development because of the jobs and opportunities it can provide. While the promise of business partnerships and prioritization of Black businesses during construction is a promising start, the long-term commitment, and outcome, will be even more telling.