Disease threatens salamanders in Great Smoky Mountains

Photo courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey

The Great Smoky Mountains is the most visited national park in the United States. When most people visit the park, they look for bears, deer or the occasional snake. Yet one of the species that has gone unnoticed by the casual visitor is now in danger of extinction.

The salamander calls the Smokies its home, with more than 18,000 of the little creatures per hectare of land in the Appalachian Mountains. The Great Smoky Mountains are home to 30+ species of salamanders and the state of Tennessee has over 60, and they are in danger.

Over 30% of all amphibians are either extinct, critically endangered, or endangered and their current rate of extinction has risen 200 times the normal rate, according to a 2004 article by the IUCN Species Survival Commission.

Although habitat destruction, climate change, and over exploitation contribute to the fall of salamanders, emerging infectious diseases are hitting salamanders hard.

Batrachochytrium Salamandrivorans (BSAL for short) is a new infectious disease that is wreaking havoc on European salamanders.

This disease “has been in Europe for quite some time, although undetected,” said Davis Carter, a doctoral student in the University of Tennessee Department of Forestry, Wildlife, and Fisheries. Carter describes BSAL as “the most invasive species in the world” and says that “BSAL devours salamanders.”

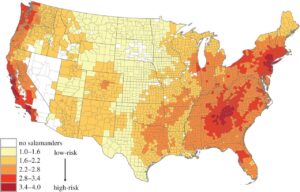

BSAL attacks the skin of salamanders. It creates spores that infect the skin and eventually destroy it. “The skin is the most important part of a salamander,” said Wesley Sheley, a doctoral student in comparative and experimental medicine, as well as a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine. Sheley explained that greater than 60 species in the US could experience BSAL and “species can be infected all over North America.”

The skin allows salamanders to maintain electrolytes, controls its immune response and allows it to breathe. But its importance could extend to humans. While “our knowledge is limited,” Sheley said, the skin excretions from salamanders could be used for medicinal purposes for humans. However, if BSAL continues to spread that research potential may be lost.

Not only would the decline of salamanders have an impact on humans, but it would also have an impact on North America and an even greater impact on the park itself. Salamanders, specifically the Eastern Newt, eat about 250 to 300 insects a day. “The Easter Newt is the most common salamander to our area,” Carter said and without them a “greater number of species would decline.” Racoons, snakes, opossum, birds and fish all eat salamanders, and if the salamander population continues to decline, other species would suffer.

Salamanders make a major, unseen part of the Great Smoky Mountains and if precautions are taken soon, one of the most visited national parks may not be there for the next generations.

However, there is hope to prevent this seemingly science-fiction scenario from becoming a reality. Carter explains that “wildlife managers need to consider what to do if BSAL is introduced and have a broad scope of different management strategies.”

Sheley said park visitors can help too.

“Disinfect your gear between sites,” Sheley said. She says to wash off your boots and other equipment between parks and trails, especially coming from another country. Another way to help is to monitor the pet trade. Partake in “responsible pet trade,” since “seven of 11 salamanders in pet trade collections tested positive for BSAL.”

Practicing responsible pet trade and disinfecting personal gear between each visit are ways everyone can help save the salamanders and subsequently save one important part of the Smokies.