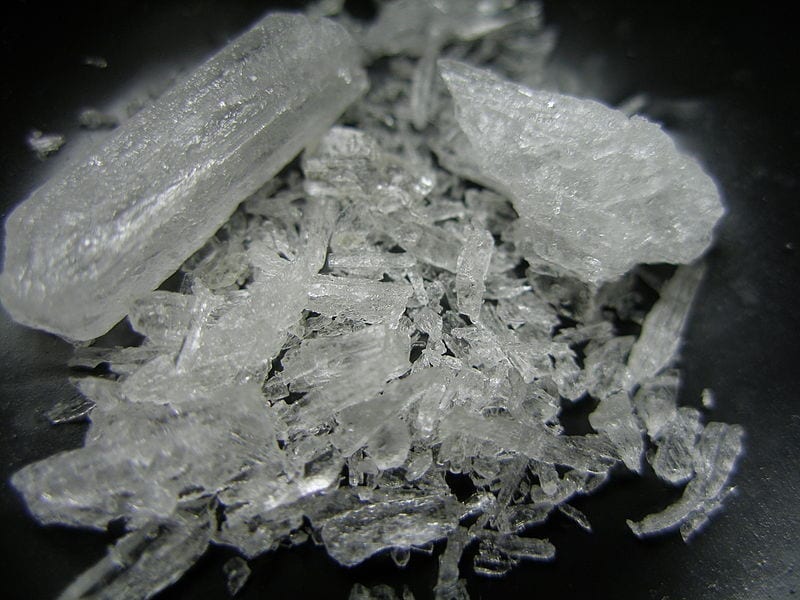

A Complicated Meth: Pharmacy regulations confusing, unhelpful in battle against methamphetamine

“I always stocked up on Sudafed,” Blackwell said. “But one day that labeled me as a criminal.”

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In the United States, nearly 50 million people suffer from nasal allergies. Waking up to a congested nose is an experience many Americans understand.

East Tennessee resident Nancy Blackwell is among that group. Suffering from allergies since she was a child, Blackwell has depended on relief from one particular drug.

“Sudafed is the only thing that works for me,” Blackwell said.

Looking for relief, she often finds herself headed to the nearest pharmacy. Although she is no stranger to the usual “behind the counter” routine, Blackwell recalls a time where she felt having allergies was “almost a crime.”

“I always stocked up on Sudafed,” Blackwell said. “But one day that labeled me as a criminal.”

She entered her local pharmacy, only to find that the Sudafed was not in its usual spot. Upon asking a clerk for help, she was directed to the pharmacy.

“I walked up to the pharmacist and told her what I wanted,” Blackwell said.

The next thing she knew, her driver’s license was being logged into a computer data base, questions on her use of Sudafed and her condition were demanded and a feeling of criminal intent surrounded her.

“I understand why they do it,” Blackwell said. “But I’m no criminal. I just want some relief.”

See more related stories:

[efssidenav ]

[efssidenavli link=”https://tnjn.com/2017/12/13/one-step-time-former-drug-user-becomes-counselor/” title=”Profile of a drug abuser-turned-counselor” active=”” divider=””/]

[/efssidenav]

[efssidenav ]

[efssidenavli link=”https://tnjn.com/2017/10/26/spacemen-drug-epidemic/” title=”Cleaning up meth labs in East Tennessee” active=”” divider=””/]

[/efssidenav]

[efssidenav ]

[efssidenavli link=”https://tnjn.com/2017/12/13/old-yellow-tape-hazelwood-road-meth-houses-remain-long-meth-makers-leave/” title=”What happens to the meth houses?” active=”” divider=””/]

[/efssidenav]

Blackwell’s story resonates with many who suffer from severe allergies. Today, pharmacies are required to verify identification from the buyer of any product containing pseudoephedrine and to answer two questions.

Do you have high blood pressure? What is your intended use?

If answered correctly, the pharmacist will ensure that the buyer has not purchased their legal limit within the past 30 days. After the buyer is screened, questioned and booked, they are free to leave with their drug of choice.

These laws were put into effect in Tennessee in 2005. The regulations stemmed from an epidemic that has plagued the state, as well as the country, for years.

Reason for implementation: hinder and ultimately stop the illegal production of methamphetamine.

Efforts to control the sale of pseudoephedrine date back to 1986. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) introduced legislation that would make the drug a controlled substance. Under this label, individuals would need to present a prescription to purchase.

Consumers complained. Lobbyists fought the change. Ultimately, the legislature denied the label change and continued the approval of over-the-counter sales.

Tennessee Bureau of Investigation’s Danger Drug Task Force Director Tom Farmer recounts the sudden restrictions in the law and the impact it has had on the country since.

“Law enforcement across the country were asking ‘What are you [legislators] doing’?,” Farmer said. “We knew then that this was going to be a huge problem.”

Farmer’s prediction would come true. Since the initial denial, DEA has reported an increase in the amount of methamphetamine seizures. In 1986, 234 kilograms of methamphetamine were seized, compared to 2,946 kilograms in 2014 in the United states.

After 20 years in law enforcement, Farmer has seen these statistics play out first hand, watching meth users and manufacturers repeatedly getting arrested, to nearly losing their lives in explosions, only to return to their illegal practices.

Frustrated, overwhelmed and over budget in his enforcement efforts, Farmer has shifted his attention from this constant cycle. His theory, summed up in just a few words, may be the key in solving Tennessee’s meth problem.

“You stop the sale of pseudoephedrine,” Farmer said. “You stop the meth.”

Though frustrating, there has been progress in diverting sales of pseudoephedrine. Nancy Blackwell’s experience on a stuffy Spring morning was the result of the Tennessee Meth Act of 2005. This law required all businesses that sold products containing pseudoephedrine to log and track each sale.

The law also limited the amount a consumer could purchase within a 30-day period. This new tracking database would work two-fold in providing businesses with the means of knowing who they can and cannot sell to, as well as providing law enforcement information on repeat buyers, which might help in tracking down meth makers.

Generally, the tracking system has worked as intended. However, just as bacteria react to antibiotics, drug abusers have begun to adapt to and overcome their new obstacle.

Farmer’s agency began seeing a steady increase in meth production across the state, but no pharmacy data to support it. During lab seizures, boxes of pseudoephedrine were always found in the area. But when referencing the suspects to the tracking system, little to no information was provided.

A new type of criminal emerging. The most common name: smurf.

“We found that our suspects were picking up random people, often homeless off the street,” Farmer said. “They’d drop them off to different pharmacies to buy the pseudo for them.”

“Keep the change” was the smurf’s motivation. Their only job was to buy as much pseudoephedrine as they could with the money that was provided. If there was change left over, their services were paid from that.

A pharmacist in East Tennessee, who has been in the industry for nearly two decades, has had their share of suspicious customers. To protect their identity, the pharmacist chose to speak under the condition of anonymity. We’ll call this pharmacist Miller.

Miller recalls the sales of pseudoephedrine products a “battle between job and ethics.”

When a person suspected of drug abuse seeks to purchase the product, they are met with the same process as any other customer. However, Miller’s moral judgment has provided different tactics.

“There’s been times that I’ve hidden the medicine,” Miller said. “If I see the same people come in to buy Sudafed, I’ll just tell them we’re out of stock.”

Though admirable, these morals do not coincide with standard business practices. Company executives require their pharmacists to sell the product that the customer requests, in accordance with current laws.

“If they have a valid ID and are not over their sale limit, we’re required to provide the product,” Miller said. “Professional judgement is allowed, but not beyond the scope of the law.”

Following current law, pharmacies across the state continue to sell pseudoephedrine to individuals meeting their legal limit. As new entries are put into the system, tracking becomes more difficult than ever.

Smurfing was the new enemy.

“This changed everything,” Farmer said. “How could we possibly track a system like this?”

Determined to kill the root of the meth epidemic, Farmer’s theory of sale prevention never left his mind. It was more apparent that current regulations were not enough. Farmer has since shifted his focus to lobbyists in Washington D.C., hoping to enact the legislation that was struck down in 1986.

The battle has moved from meth labs, drug abusers and smurfs, to federal buildings, legislators and lawyers. However, several attempts by Farmer’s agency to require pseudoephedrine to be labeled as a scheduled narcotic have failed.

“The benefit outweighs the harm” of pseudoephedrine, legislators argue. After all, 50 million people are suspected of suffering from nasal allergies.

Farmer argues that, while he does not deny the need for pseudoephedrine, multiple alternatives are designed to be just as effective.

“There’s no cure for the common cold,” Farmer said. “But pseudo is not the only relief. There are safer options out there, but those won’t line the pockets of the pharmaceutical companies.”

One of these options is a form of pseudoephedrine that cannot produce meth. A brand titled, “Nexefed” claims to produce the same results as Sudafed, without the chemical properties that allow meth production.

Miller has used this brand as an additional tactic to curb drug abusers. However, price tends to be the deciding factor.

“I wish Nexefed was the only option,” Miller said. “But when you compare the price to regular Sudafed, there’s no contest. Sudafed is always the better deal.”

As the war against methamphetamine continues to grow across Tennessee, soldiers like Farmer and Miller are left only with the powers they are granted. Met with opposition, they find their efforts against meth hindered by powers beyond their control.

Those powers revolve around pharmaceutical companies and lobbyists in Washington D.C. with a common goal expected of all businesses: money. However, this goal is gripping the state of Tennessee, as well as the nation, in an epidemic that’s losing the grip from those trying to combat it.

Farmer vows to not give up. Now facing imports of methamphetamine from other countries, his efforts grow more challenging every day.

“I will keep making the calls, taking the trips, writing the letters, until I’m relieved of my duties or dead,” Farmer said. “I took my oath many years ago to protect and serve and I’m not about to slow down now.”

After 31 years of combative efforts, Farmer’s progressive nature will be put to the test. As the United States faces threats and challenges across the globe, an internal war has been waging over three decades.

“I don’t know where it will all go from here,” Famer said, “but I hope I live to see the end of it.”

Don’t we all.