Deciding Factor: Homelessness in Knoxville

A study conducted bi-annually for 20 years shows that the homelessness rate in Knoxville has been steadily increasing since the early 1980s, according to data compilations collected by Dr. Roger Nooe, the director of social services for the Knox County Public Defender’s Office.

A homeless man in Downtown Knoxville shows his prosthetic leg as he sells the Amplifier newspaper. // Photo by Ryan McGill

The surface of his desk and side tables are filled with carefully balanced piles of manila envelopes and stapled information packets. The bookshelves that line the walls overflow with literature about philosophy, law and data collection. Dr. Roger Nooe rifles through the stacks, brow furrowed, in search of data compilations that he has gathered over the years.

A study conducted bi-annually for 20 years shows that the homelessness rate in Knoxville has been steadily increasing since the early 1980s, according to data compilations collected by Nooe, the director of social services for the Knox County Public Defender’s Office.

In an attempt to help lower the rates, Nooe said that he assembled a team to walk the homeless hotspots of Knoxville and survey the people they came across in 1985.

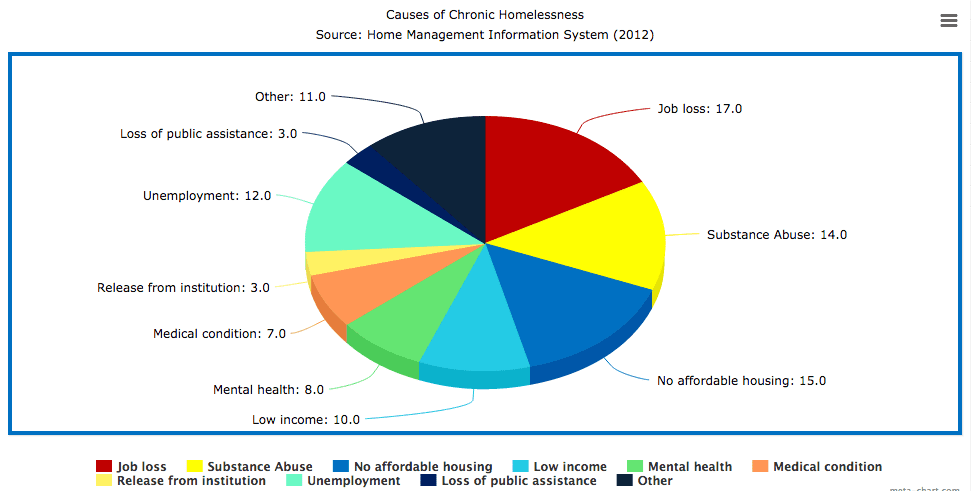

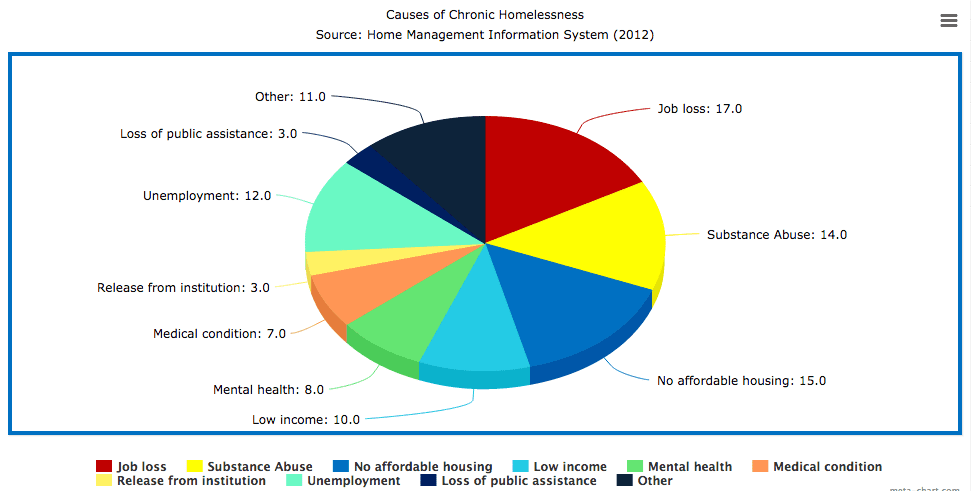

After 20 years, he created the Home Management Information System, a web database containing all the names of the people he surveyed. Today, the system contains information from 32,000 people.

There are three types of homelessness—acute, episodic and chronic, according to Nooe.

The acutely homeless, the largest percentage of the homeless population, are those that are homeless due to some sort of trauma, such as divorce or job loss.

Next, the episodically homeless, or the “couch population,” are those who often receive some kind of disability stipend from the government or have seasonal jobs and are likely to stay with a friend or family member.

Last, the chronic homeless, the smallest group, is comprised of people who have been homeless either for over a year or four times in the last three years, and often have some sort of disability, such as mental illness or a substance abuse problem.

Drew Burker, a political science major, said that there is a heckling problem on UT’s campus, and the best way to prevent this is to place the burden on another city’s shoulders.

“Some of the homeless are aggressive toward students, and I think that the city should relocate them,” he said.

Nooe said the full support of the community is the key to reducing Knoxville’s homeless rates.

Just five years ago, an abandoned elementary school in South Knoxville stood on an overgrown corner lot, unused and uncared for; the broken windows and surrounding rusted fence an eyesore in the community. What was once Flenniken Elementary School, where children played four square at recess and little boys pulled at girls’ pigtails in math class, had become a local attraction for the curious and bored teenager undaunted by a privacy fence.

Nooe said he believes in the relationship between urban renewal and low-income housing. In 2011, Flenniken Landing opened in Knoxville.

Flenniken Landing was renovated into low-income apartments, providing 48 living spaces for those classified as at-risk for homelessness, according to its website.

A year prior to this was the opening of Minvilla Manor, which contains 57 apartments that serve the same purpose.

Additionally, Nooe said local ministries such as Knoxville Area Rescue Ministries and Family Promise Church provide temporary lodging for many homeless families.

Maggie Manning, a volunteer at Family Promise, said that the cyclical nature of the program is often hard on families.

“They stayed overnight in a different church every week. They kept their belongings in suitcases that could be moved from place to place,” she said. “It was hard on the kids.”

Nooe said that solving homelessness is a community challenge, and the only way for a major shift in trends to occur is for local ministries and organizations to unite their individual efforts.

“It isn’t going to be solved by ministries and social services alone,” he said. “It really takes people to get involved and care about other people.”

Nooe has spoken to a number of people who have faced homelessness and beaten it. He often makes it a point to ask them about the deciding factor in their situations.

The response he most often receives: “Somebody believed in me.”

This article has been edited by the editorial staff of the Tennessee Journalist. For the unedited version, go here.